Fall of the Giants: September Pick of the Month

BY ESME GARLAKE

All images: Esme Garlake

Giulio Romano at Palazzo Te

The Palazzo Te in Mantua, Italy, is one of the most fascinating places I have ever visited. The suburban palazzo was designed and decorated by Giulio Romano, the Roman artist who was the principal heir to Raphael’s workshop (following his teacher’s untimely death in 1520). In 1524, Giulio moved to Mantua to start working as the court artist for the wealthy Gonzaga family; this move, in part, came from a desire to break away from the intense competition in the Roman art scene. In Mantua, Giulio’s status as Raphael’s heir and colleague granted him creative freedom, allowing him to show off what he could do as an artist. His patron, Federico II Gonzaga, benefited greatly from this arrangement, too; it was not only a public declaration of links between the Gonzaga family and the great artists of Rome, it provided Federico with an astonishing Palazzo (architecturally, artistically, conceptually) which has come to be seen as one of the masterpieces of Mannerism.

One word which best describes the Palazzo is ‘playful’ - not a word which we might associate automatically with Renaissance buildings (which lots of people might see as stuffy or conservative). But Giulio Romano is constantly having a joke in Palazzo Te: even in the outside architecture, he intentionally includes ‘false’ windows, and makes the walls look as if they are made from stone (even though they are actually all made of plaster). He wants his visitors to question what is around them; this doesn’t have to be in a pretentious way, because it often feels more like he’s saying ‘wink, wink, nudge, nudge’ to us. Inside, his frescoes are consistently strange and unexpected: in the famous Hall of the Horses (in which Giulio depicts Federico II’s favourite steeds in realistic portraits), one of the horses looks down at us and - startled - catches our eye. Above them, cherub-like figures (known as puttini or amorini) play in decorative foliage in ridiculous, topsy-turvy poses. In another room, we look up at the ceiling and stare straight up at Apollo’s bare bottom, exposed by the angle; Giulio places us directly underneath him.

Room of the Giants

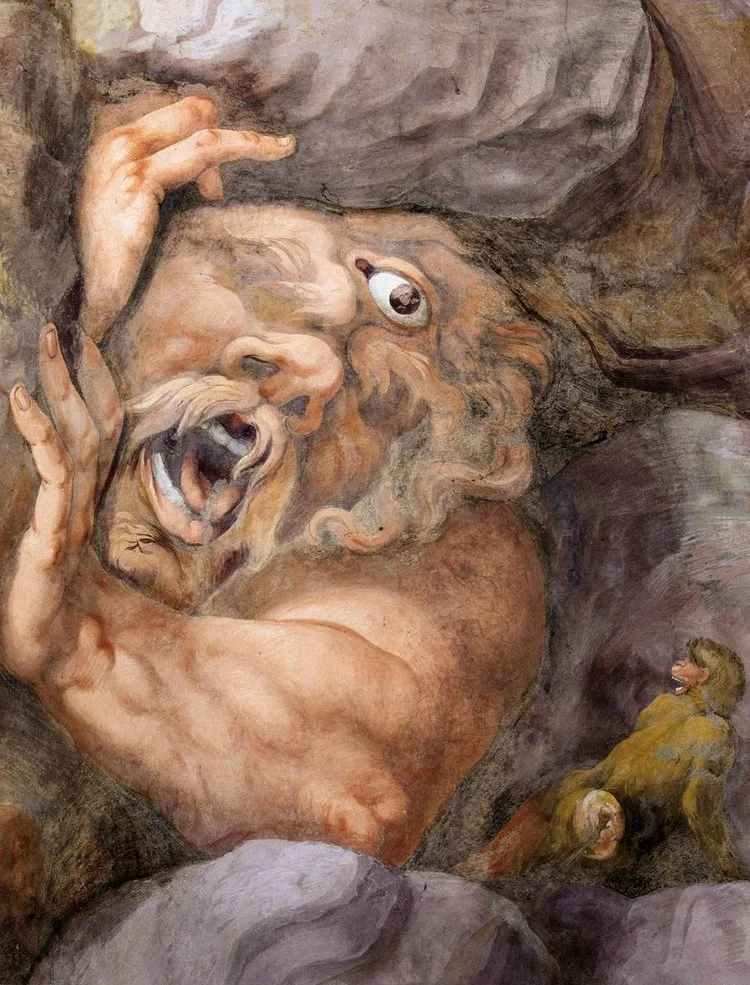

For most visitors, however, the showstopper of the Palazzo Te is the Fall of the Giants room. Giulio depicts the ancient Greek myth of the Fall of the Giants, in which the God Zeus destroys the Giants with thunderbolts. The Latin poet Ovid included the episode briefly in his poem Metamorphoses, recounting that the Giants attempted to seize ‘the throne of Heaven’ by piling ‘mountain on mountain to the lofty stars’ (provoking the fatal retaliation from Jupiter, the Roman Zeus). Ovid also goes on to explain that the human race came from the blood from the Giants, and also shared their desire for ‘savage slaughter’. Giulio’s depiction is astounding: the room is a 16th-century version of an immersive Virtual Reality experience.

When I first walked into the Fall of the Giants room in Palazzo Te, Mantua, like most visitors, I simply stood there in awe. Enormous frescoes of giants and collapsing buildings surrounded the viewer. Whilst we usually see frescoes from far away (looking up from the floor at frescoes on the ceiling), here the images are right in front of us; at eye-level, a giant’s huge hand, head, or foot might be (to put it into scale) nearly the size of some of the shorter visitors to the room. The corners of the square room are rounded - an intentional choice by the artist and architect, Giulio Romano - which seems to cancel out any logical sense of architecture. We find ourselves immersed in a scene of chaos and collapse.

Explore the Fall of the Giants in 360 degrees here:

As I stood amidst the apocalyptic chaos of Giulio Romano’s Fall of the Giants, I immediately felt a parallel with our situation in the climate crisis today. The room shows a world collapsing instantaneously; in many ways, the destructive scene is similar to what we are facing today. According to the ancient myth, the Giants were an ‘earth-born’ race of great strength and aggression - sounds familiar, right? For most of us, it is almost too difficult to truly comprehend just what the impact of the ecological and climate emergencies will look like, even though the consequences are already having devastating impacts across the world, particularly in the Global South. The impact is not just flooding or slightly warmer weather; it is crop failure, mass migration (a predicted 1.2 billion migrants by 2050), water shortages and droughts, and the wars and conflict which come along with this. Many of us in Europe this year have had a taster of what it means when temperatures rise - from children being forced to stay home from school during the hottest days to wildfires occurring across Europe (destroying an area equivalent to one-fifth of Belgium, according to data from the European Forest Fire Information System).

The Fall of the Giants can tell us about human reactions to images of disaster. Giulio has created an immersive world for his viewers; it is one of high drama, but undoubtedly also of intrigue and excitement, almost like a Renaissance version of an action film. And whilst it is a disaster for the Giants, it certainly is not for the Gods looking down from above. Who are we meant to identify with? If the Gods are the ‘goodies’, looking down on us, what does it mean for us to be (literally) on the same level as the Giants? I wonder whether Giulio is encouraging us to consider our mortality, our earthly state, and the fragility of a civilisation. This more reflective interpretation could be a helpful - albeit scary - reminder for modern viewers today.

The civilisational collapse that we face today, however, is not a result of divine powers, but rather the result of human activity. It can sometimes feel, of course, that the huge corporations seem to run the world, almost as untouchable and undefeatable as the Gods. However, people across the world are starting to realise that this power can - and must - be challenged, and that ecological and climate disasters are not inevitable. Ordinary people are coming together in collective action to demand meaningful and drastic change. This room also acts as a fantastic reminder of the human capacity for imagination, a skill which must be at the heart of any struggle for climate and social justice. The room is a testimony to Giulio Romano’s desire to create an immersive space which shakes up our perceptions of reality, and to encourage us to exercise our ability to see the world in new, creative ways.

Although Giulio Romano filled this room with surprises, there is one element which he certainly did not plan. Around the room, hundreds of graffitied names from centuries ago (dating even further back than the 1700s) are chiseled into the walls. It is vandalism, of course, however for modern viewers it is fascinating to see these names and dates, which seem to connect us to people from the past who have also stood in the same spot, marvelling at the Giants and the Gods. We are not only looking back to the generation of Giulio Romano, but the generations between then and now. Intergenerational thinking is a skill, and art history helps us learn it. With this skill, we can look to the future, too, and ask what kind of legacy we want to leave behind for future generations.

Esme Garlake (@eco_art_historian) is a London-based art historian specialising in 16th-century Italian art and ecocriticism.

September 2022